PlayStation and the Art of Advertising Escapism

Back in the early days of the console wars, owning a PlayStation wasn’t just about gaming but a fever dream of the after-hours, tucked between MTV broadcasts and the allure of midnight piracy. In the ’90s and early 2000s, before every piece of advertisement was filtered through an algorithmic focus group, Sony had a different idea in mind. Early PlayStation commercials were definitely a case of their own. When a console ad features a man confessing that he’s led a double life, or a talking duck inside a portal, you know you’re in freaky territory. PlayStation commercials were the weirdest teenager in the family, and I’m loving every second of it!

The late-‘90s advertising landscape was anarchic, full of brands eager to push boundaries for attention, even if they didn’t always know how to do it effectively. Imagine a time where Pepsi thought it would be a good idea to give away a Harrier jump jet worth millions of dollars. It was the actual wild west: no rules, no filters, no apologies. I can’t stress enough the surrealness of mainstream advertising at the time: wild, often absurd and definitely untethered to reality.

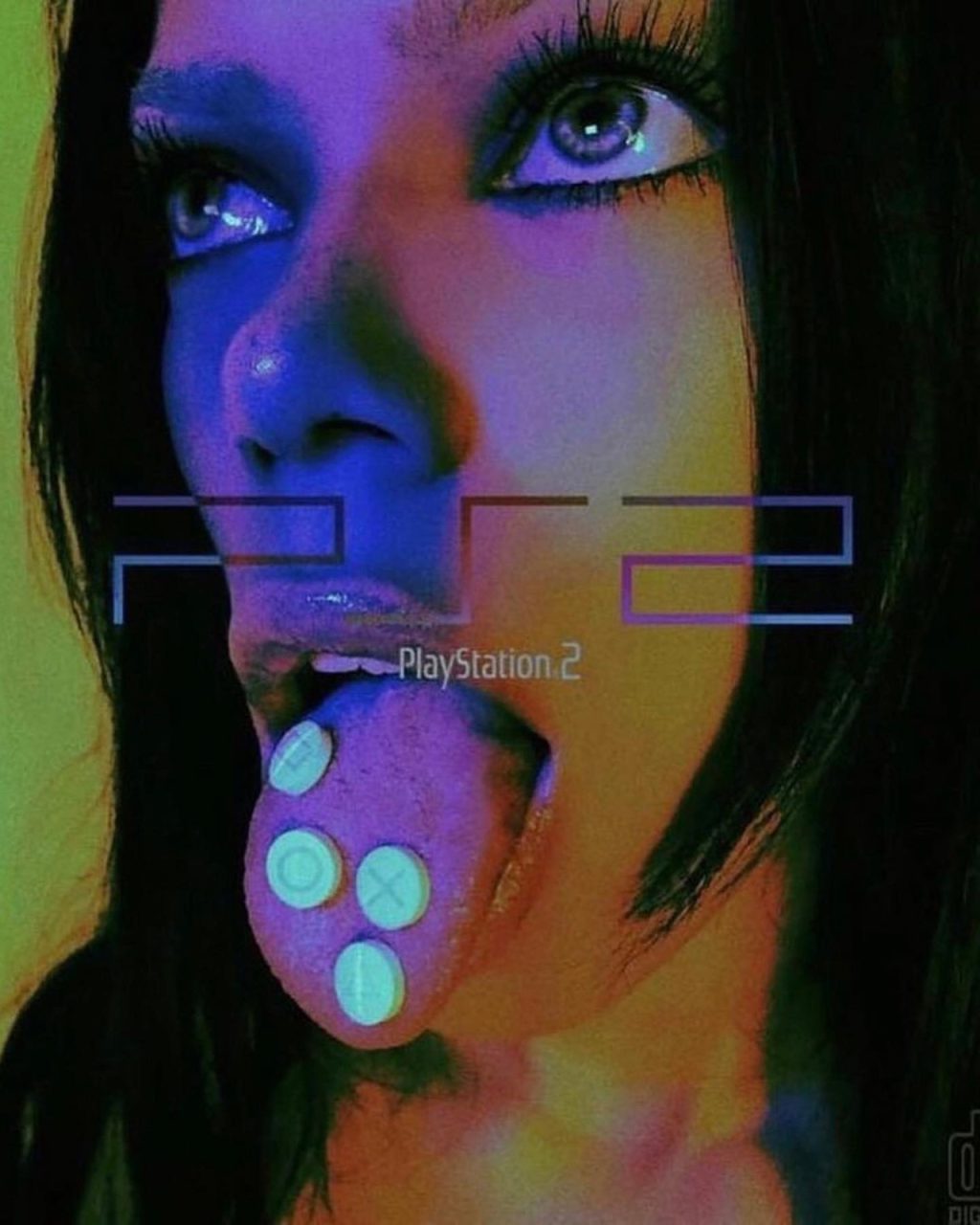

PlayStation’s early ads fit perfectly into this chaos, but with a twist: they didn’t pander to the mainstream. Where Pepsi’s stunt was winking at suburban youth, Sony’s campaigns embraced club culture, industrial design and countercultural angst. Before the internet and social media homogenized marketing, a game console’s commercials could be provocative and edgy but still make the cut for prime-time advertising.

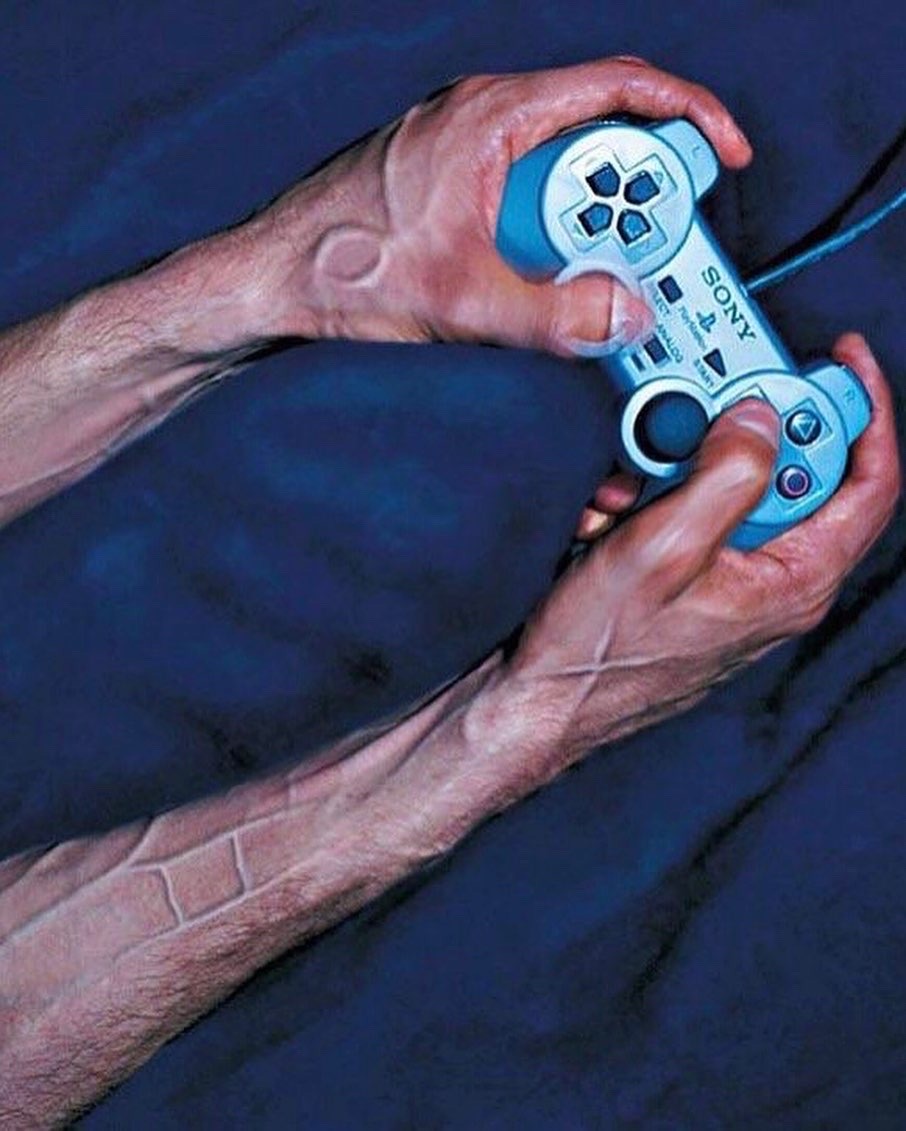

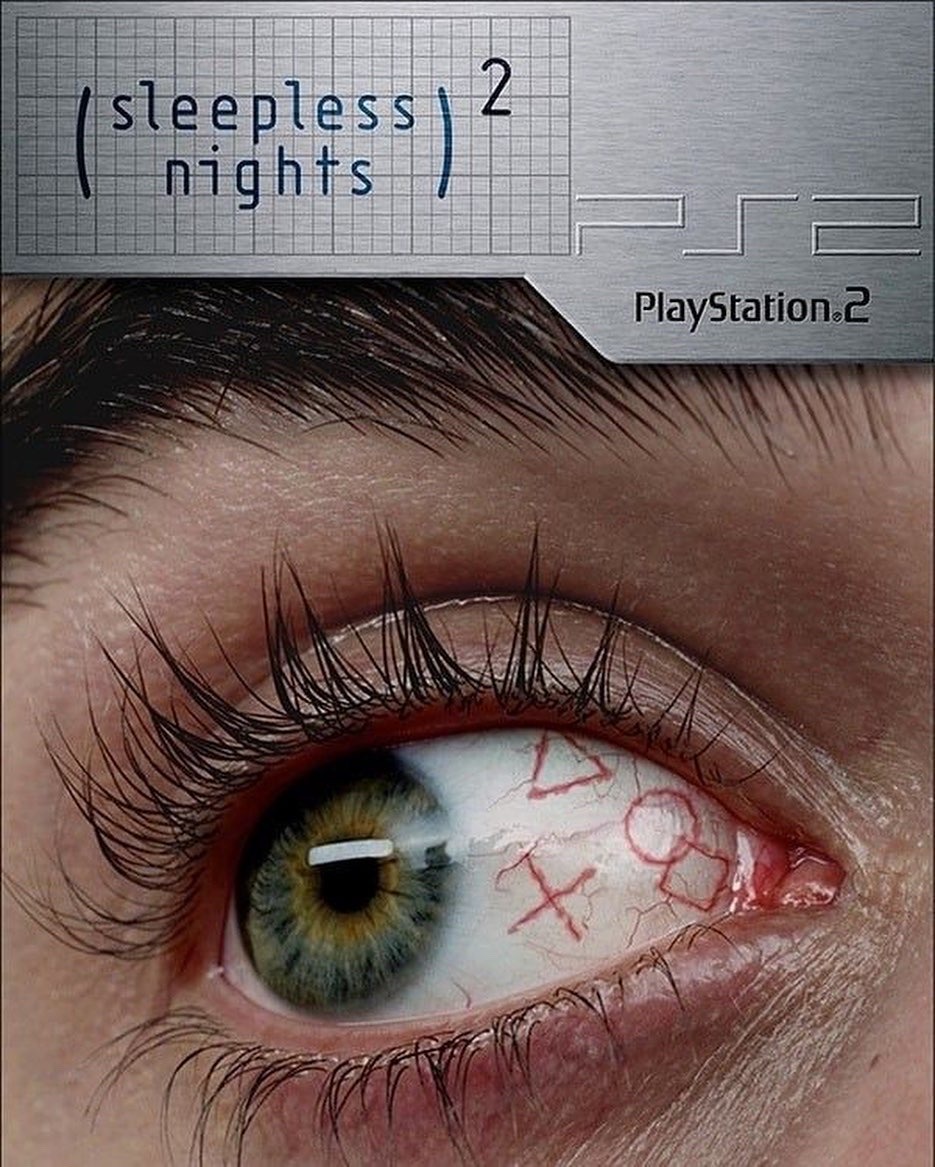

This curated universe captured attention, and when the PS1 arrived in 1994, it changed gaming’s demographic. It ditched cartridges for cheap CD-ROMs and invited third-party developers to experiment with 3D worlds. This wasn’t just for kids, and Sony was eager to get the message across. One ad captured this ethos better than any design brief. Over a minute, nineteen everyday people confess to commuting, doing “hoi polloi” jobs, then living violent, morally dubious, and ecstatic lives after dark. The script ends with the tagline “Do not underestimate the power of PlayStation,” and the spot quickly became the most awarded commercial of 1999/2000. Marketing scholar Scott Steinberg praised its ability to transcend advertising, noting that the film’s casting and dialogue “capture every man’s desire to transcend the boundaries of mundane life” In other words, the PS1 tapped into the escapism culture we know today. Just like that, PlayStation got the reputation as gaming’s punk movement.

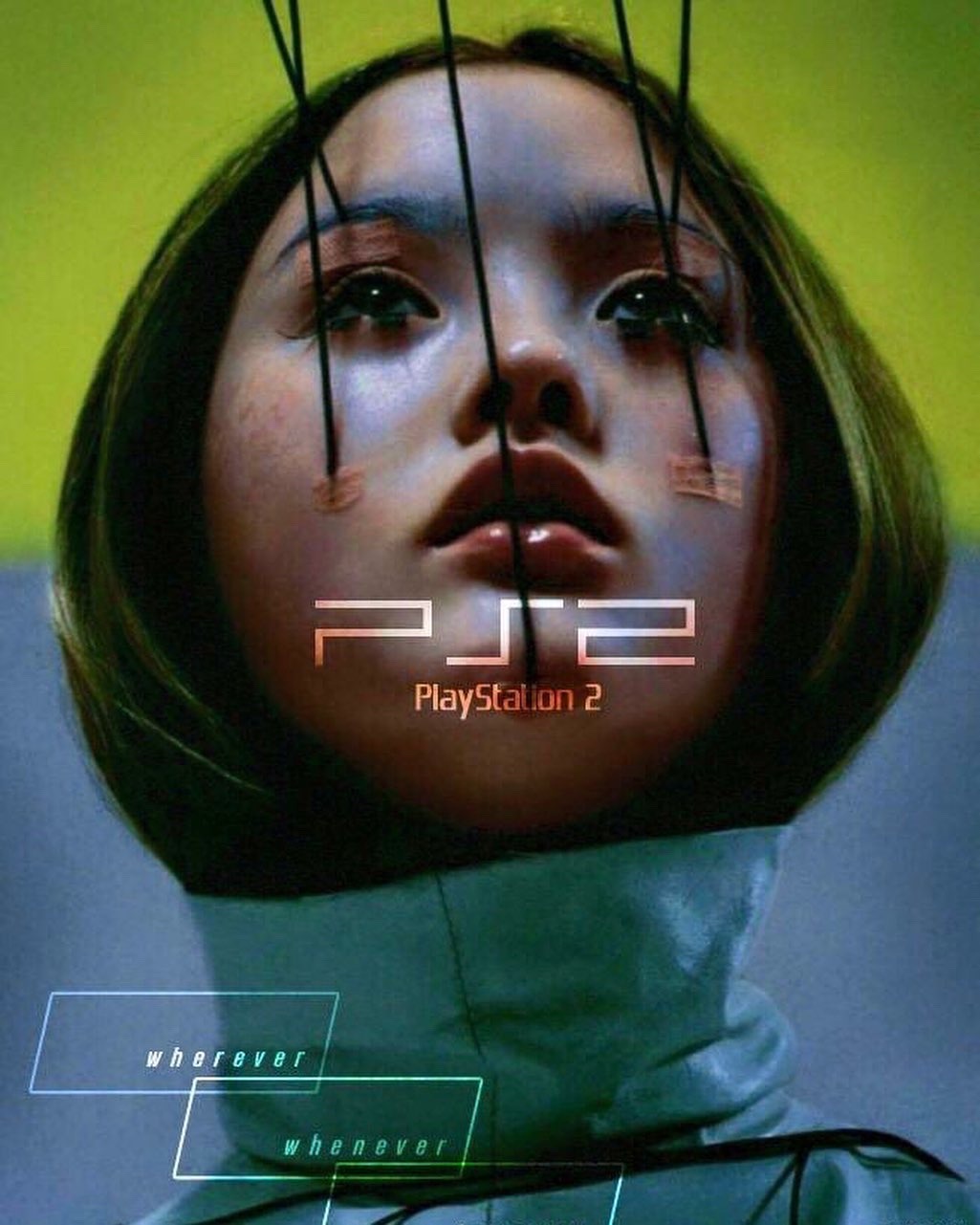

Sony’s willingness to hand its brand to directors turned commercials into miniature art films. David Lynch directing a console ad sounds like an internet meme, but it actually happened. In 2000, he made “Welcome to the Third Place,” a monochrome PS2 commercial filled with flames, glowing women, organ-like objects, and a talking duck. A write-up of the ad notes that Lynch “crafted a fragmented narrative where the boundaries between reality and the virtual world were blurred,” featuring “bizarre characters” like a floating head and a fiery woman. The aim was to convey gaming as a hallucinatory journey rather than a product demonstration. Lynch was the only person who could communicate such a message, and he certainly did.

Lynch wasn’t the only director to bend reality for PlayStation tough. Print ads for the PS2 referenced Trainspotting, The Matrix, and Requiem for a Dream, juxtaposing mundane life with surreal abstractions. One controversial flyer distributed at Glastonbury in 1996 declared the console “More Powerful than God,” foreshadowing Sony’s taste for subversive slogans. The underlying premise was simple: real life is boring; PlayStation is a portal to uncanny realms.

What made these commercials feel so radical was their embrace of dream logic. They didn’t summarize a game or list features; they evoked moods and let viewers project their own fantasies. Today’s ads, constrained by social‑media attention spans, rarely allow such digressions. Even Lynch recognized the cultural shift. In a 2008 interview, he railed against watching films on phones, saying: “You’ll think you have experienced it, but you’ll be cheated. It’s such a sadness, that you think you’ve seen a film, on your f**king telephone. Get real!” His rant wasn’t just about screen size; it was about the context in which we consume art.

So ask yourself: When was the last time an ad felt memorable? No, really, ask yourself, and you will find that it was not only AAA studios that gentrified art out of commercials, but also us, getting lazy with how we curate and consume. It’s honestly crazy to see how, despite having more access to creative tools than ever, creativity somehow keeps slipping out the door. Welcome to the modern day Schrödinger’s cat paradox.