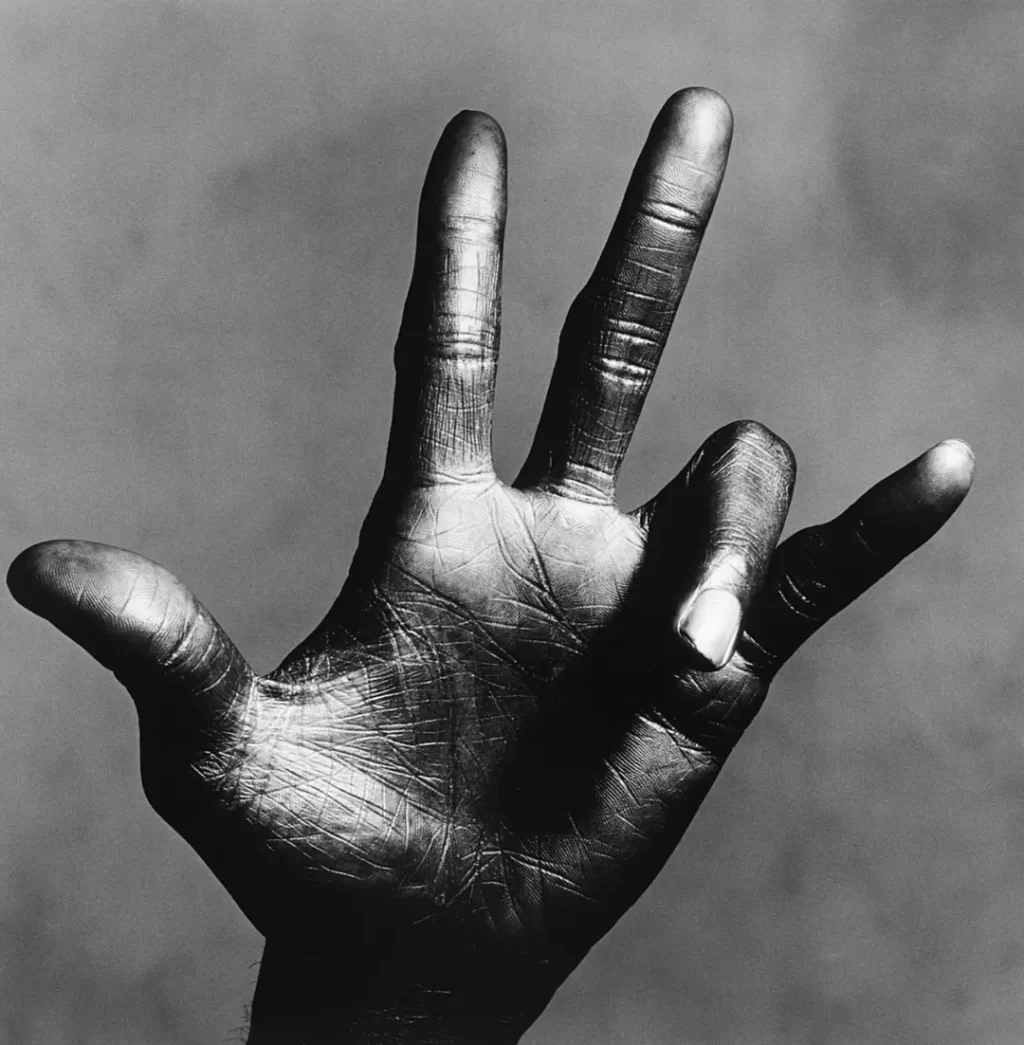

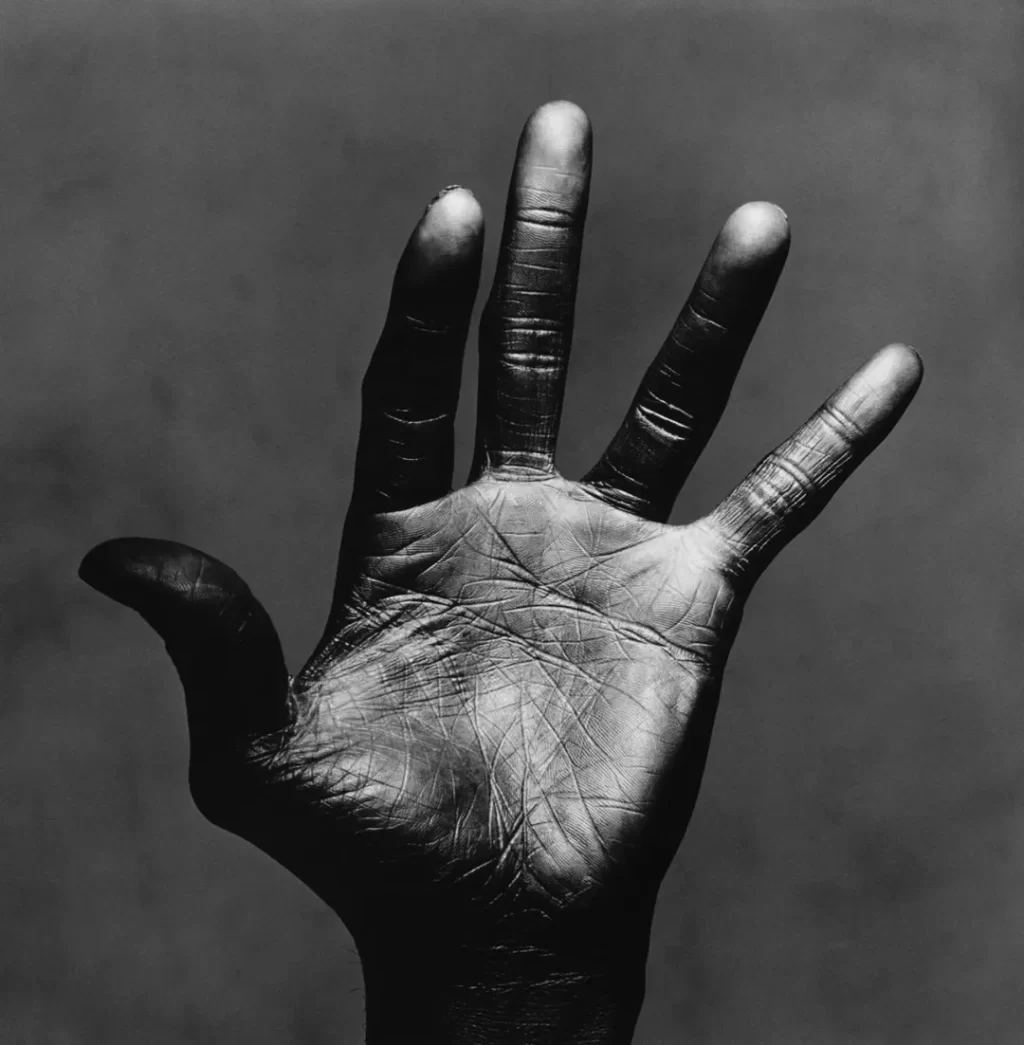

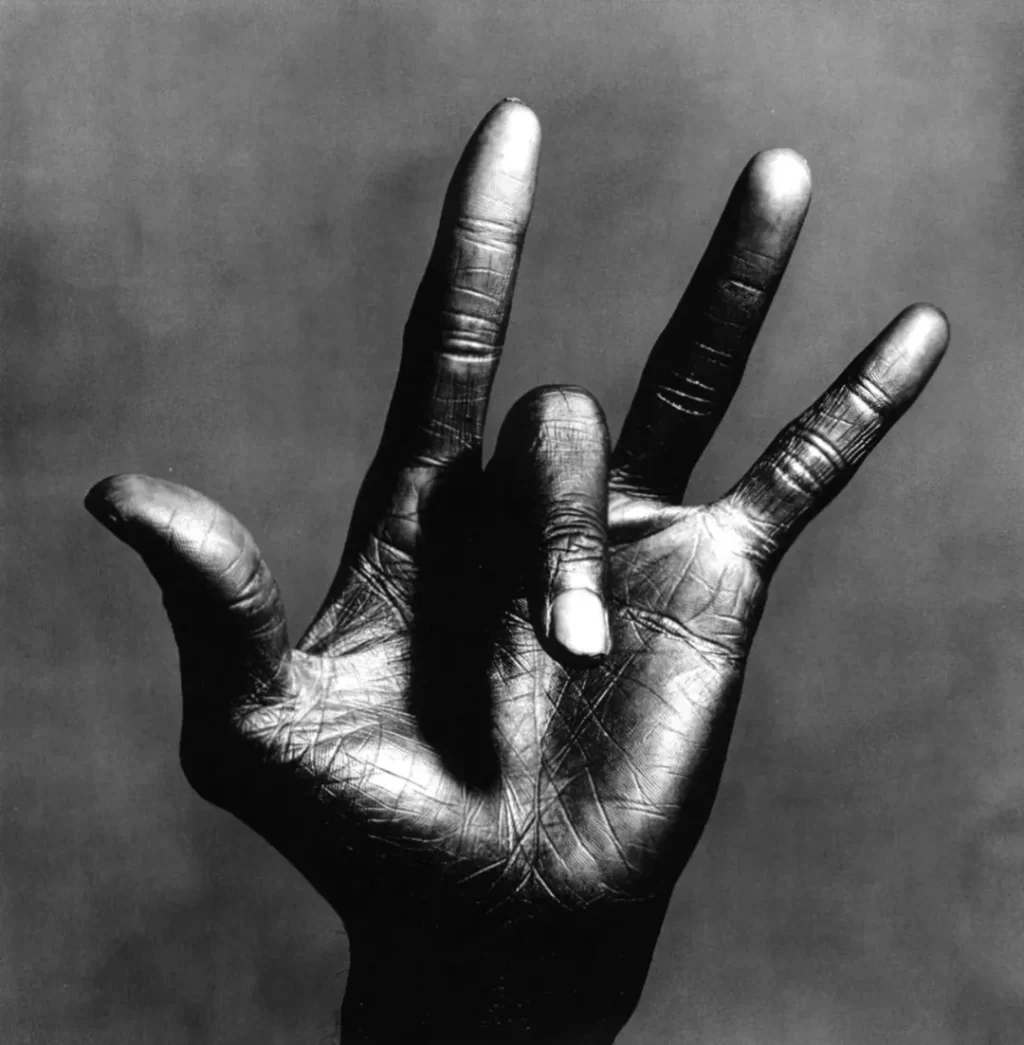

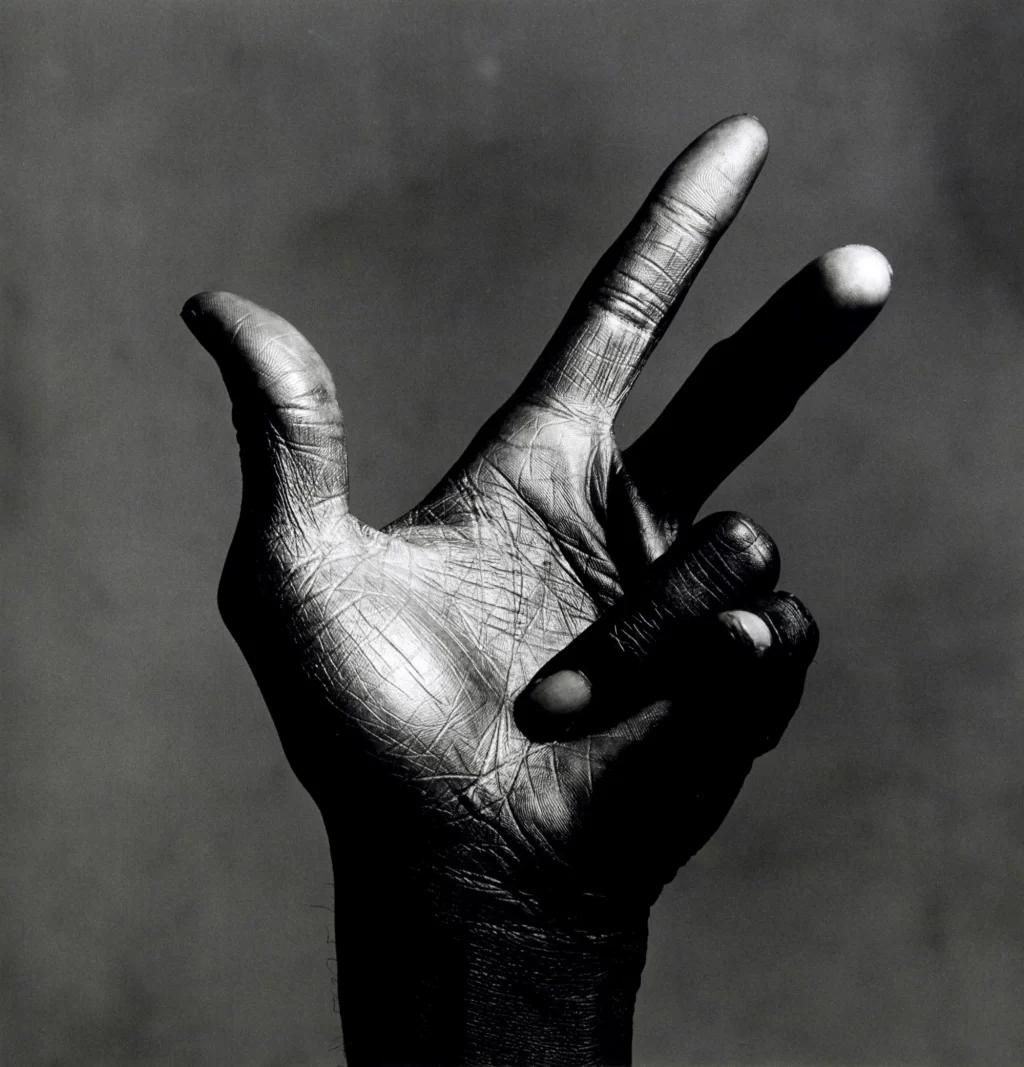

The Day Irving Penn Made Jazz Stand Still “Hand of Miles Davis”

Greatness often has an uncanny relationship with serendipity. One moment might feel awkward, even antagonistic; later it is recalled as a defining stroke of genius. Irving Penn and Miles Davis, creative titans in their own fields, met exactly in such a moment. What makes a photograph legendary? Is it the subject, the photographer, or the setting? Penn’s series titled “The Hand of Miles Davis” suggests that greatness can be held in the palm of a hand. It exposes the jazz legend’s weathered palm, raw and open to imagination, and ambiently translates music into photographic form. Want to talk about one of the most iconic album covers of all time?

Penn is remembered as one of the 20th century’s most influential photographers. He came to photography almost accidentally after studying design and working in commercial art. At the start of his career, art director Alexander Liberman of Vogue taught him to use an 8 × 10-inch camera and allowed him to experiment on the printed page. Penn’s fashion photographs blended portrait and still life; he rejected elaborate settings and placed models against plain backdrops, isolating them so that their character could speak for itself. Over time, he applied this minimalist approach to portraits of artists, musicians, and writers, stripping away cultural associations to reveal personality. This approach resulted in a distinctive visual style that set Penn apart from his contemporaries.

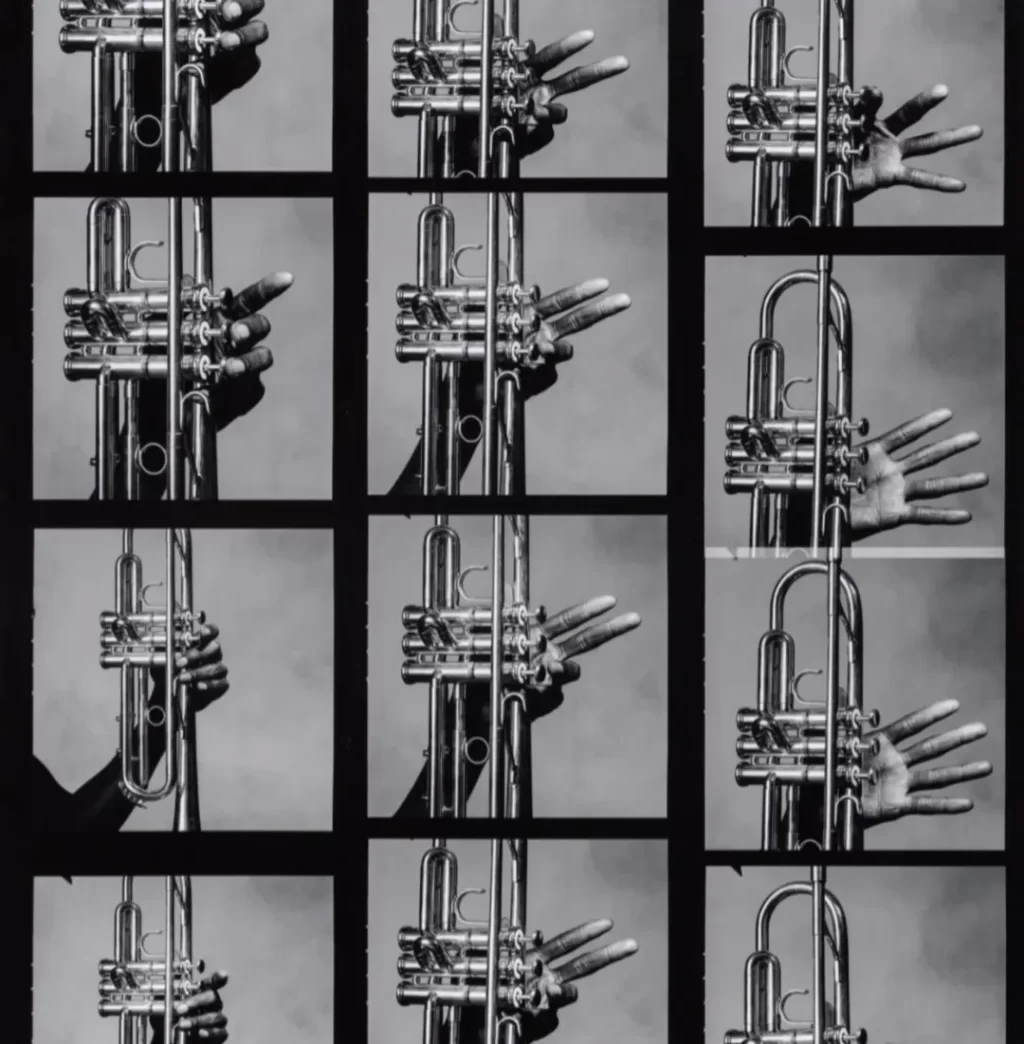

His portraits often eliminate backgrounds or faces, isolating the subject from any anecdotal context to create a pure space for experimentation. Penn’s work blurred the boundaries between commercial assignments and fine art, weaving a personal vision through fashion campaigns, advertising, and travel photographs. From this sensitivity around form and gesture, “The Hand of Miles Davis” happened. An invisible trumpet played a mute jazz solo, one that can only be heard through your eyes.

By 1986, Miles Davis had already reinvented jazz multiple times. He had spearheaded bebop in the 1940s, cool jazz and modal experiments in the 1950s, orchestral collaborations with Gil Evans, electric fusion in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and then retreated due to health issues. His comeback in the 1980s saw him employing younger musicians and pop sounds on “The Man with the Horn” (1981), “You’re Under Arrest” (1985), and “Tutu” (1986). In the official Miles Davis site’s retrospective, writer Ashley Kahn notes that the tracks on “Tutu” were created with Davis’s voice in mind, not merely as backing tracks; the record’s success owed much to this thoughtful collaboration. A food for thought.

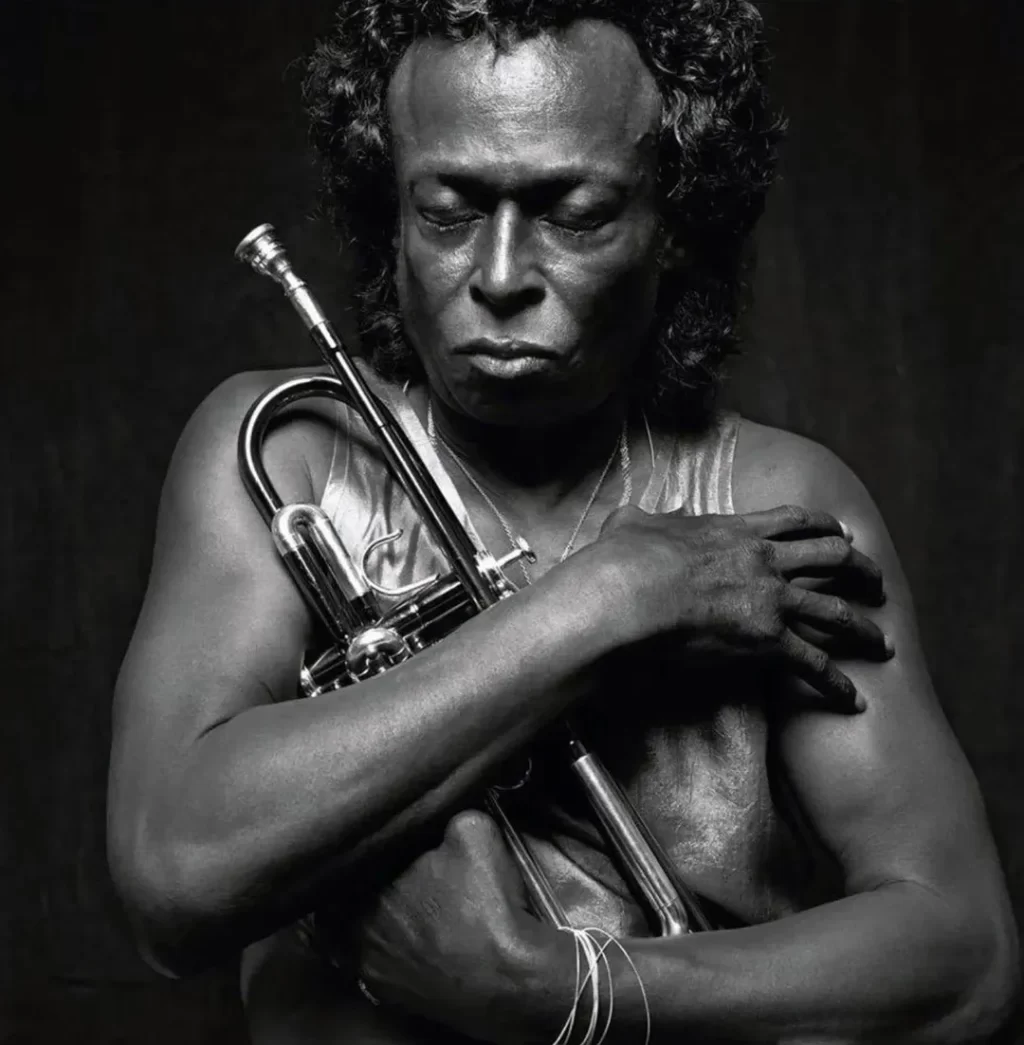

On 1 July 1986, the two met at Penn’s New York studio for the cover shoot of “Tutu”. Miles Davis brought only a few things: a hairdresser, some golden jewelry, and his infamous attitude. Penn later recalled that when he attempted to greet his subject, Davis completely ignored him. This was a clash of two titans, Conflict was a natural response. After the hair and jewelry were arranged, the musician took his place before the large-format camera. The photographer and the trumpeter engaged in a terse dance of control and consent. According to Penn’s account in a 2004 Vogue feature, Davis teased: “I bet you want me to take this shirt off?” Penn replied, “Yep.” Davis continued, “I bet you want me to take all these gold chains off, too?” Penn again said, “Yep.” For about an hour they worked in silence, the camera recording variations on a face and a hand that had defined half a century of music.

Penn’s minimalism shaped the session. He stripped away props, jewellery, and even the musician’s shirt, isolating the silhouette against a seamless background. The resulting cover photograph is a stark, black-and-white close-up of Davis’s face, lit so that every wrinkle reads like a musical score. These pictures became an integral part of the music’s visual representation. Complementary images of Davis’s hands appear on the inner sleeve and disc label and are still highly sought after.

At the end of the shoot, Penn thanked his subject. “He got up, came over to me, and kissed me on the mouth,” Penn recounted. “I didn’t know what to say. We shook hands, and he left. Later, I got the chance to know his music, and it struck me as being visual art of the most profound kind. How terrible I couldn’t share that with him then”Penn later said that after the shoot he went home and listened to Miles Davis’s music; “I was blown away by him,” he said in an interview. “That was it.”

The Tutu packaging, designed by art director Eiko Ishioka, won a Grammy for Best Album Package. The stark images by Penn, printed with platinum palladium richness, gave visual form to Davis’s abstract sound. How do you think creative tension yields profound art? In that studio on a hot July day, Penn coaxed from Davis. Serendipity, humility, tension, and trust all played their parts. But for Penn the kiss was all there is to remember.