Blacks and Whites of Masahisa Fukase Contrasting Life

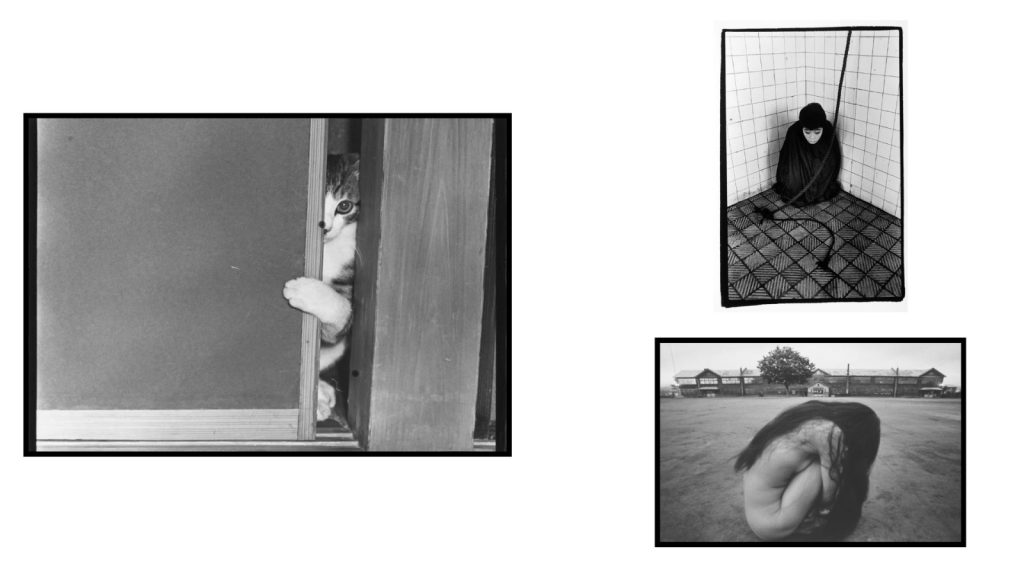

How much does our conception of the world hinge on how we love? Or even who and what we love? In the midsts of black and white hides stories of love, loss and obsession—Masahisa Fukase captures his’ in a frame knowing that the moment is fleeting no matter how hard you try to catch it. While chasing time, Fukase also chases himself in the ultimate form of selfishness that is art. Every gaze around every occasion, is a look into himself. It’s a perverse kind of attention. He solely looks to get a better look at himself. After all isn’t the mirror an essential part of a camera’s casing?

A mirror might show us the truth, but when it cracks, the truth distorts, splinters, fragments. Fukase’s life was one of reflection—on the dangerous nature of love, on the endless itch of obsession, on the unbearable weight of solitude… He was a man who loved and hated photography in equal measure for what it gave him and what it took away.

Masahisa Fukase’s eccentricity, radicalism, and experimental style can all be linked to one defining characteristic: obsession. For Fukase, photography was not merely a practice but a relentless pursuit—an extension of his emotions, his relationships, and ultimately, himself. This selfless-selfish approach reached incredible heights, celebrated for its raw intensity, but it also plummeted to haunting depths where it’s so painful that you want to avert your eyes from it.

Fukase’s life mirrored this duality. His highs were brought by love, particularly his muse and wife, Yoko Wanibe, and his lows were defined by despair. Photography became his means of communication—a tool to channel what words could not. His images spoke of intimacy, heartbreak, and isolation with an honesty that left no room for pretense. And that’s where great art happened.

The White

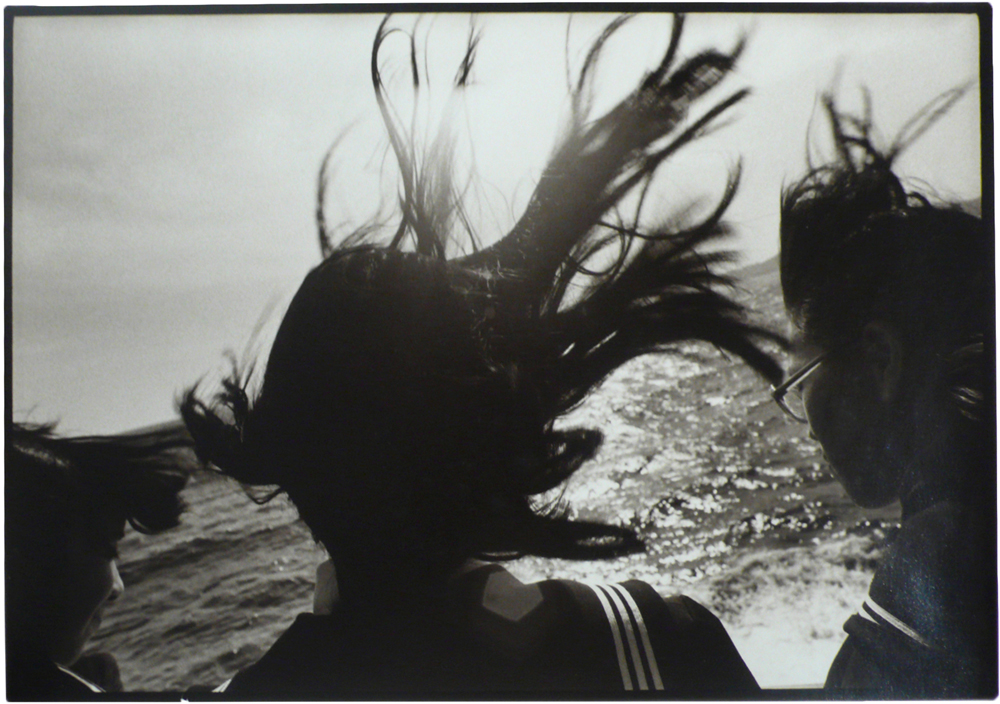

Yoko Wanibe, his second wife, was a great mark on Fukase’s life. To some extent, an obsession nearly as profound as photography. 13 years they spent together and during that time Yoko became his subject, his muse and rather his co-creator. Yoko is a willing participant. She performs, dresses up and poses. The resultant photographs are often joyous as well as sombre. She became both an echo and a contrast—a luminous figure against Fukase’s often stormy vision.

It all seems poetic in some way until you stop to think what it could be like to live with a photographer. First, you must think you’re eternally being spied upon, trying to be caught unawares, that an eye waiting to catch the true-true-you is always present, and always watching. It’s a song and dance, yet the music never really stops playing.

It is only later that you realize that it isn’t your essence that the photographer is trying to capture and distill truth from, it’s his. That each image pointed at you is really just a sublimated view of themselves, and that what they project when they point and click in your general direction is really just a reflection back of self, sometimes twisted and sometimes upside-down.

Yoko was in a position where she was in the passenger seat of her own life. So radically, in a move meant to author more control over her own life, she left him in 1976. Yoko then goes on to write an article called “The Incurable Egoist”, which ironically later became a show title for Fukase. She also distills all the time that they spent together into moments of “suffocating dullness interspersed by violent and near suicidal flashes of excitement.”

The Contrast

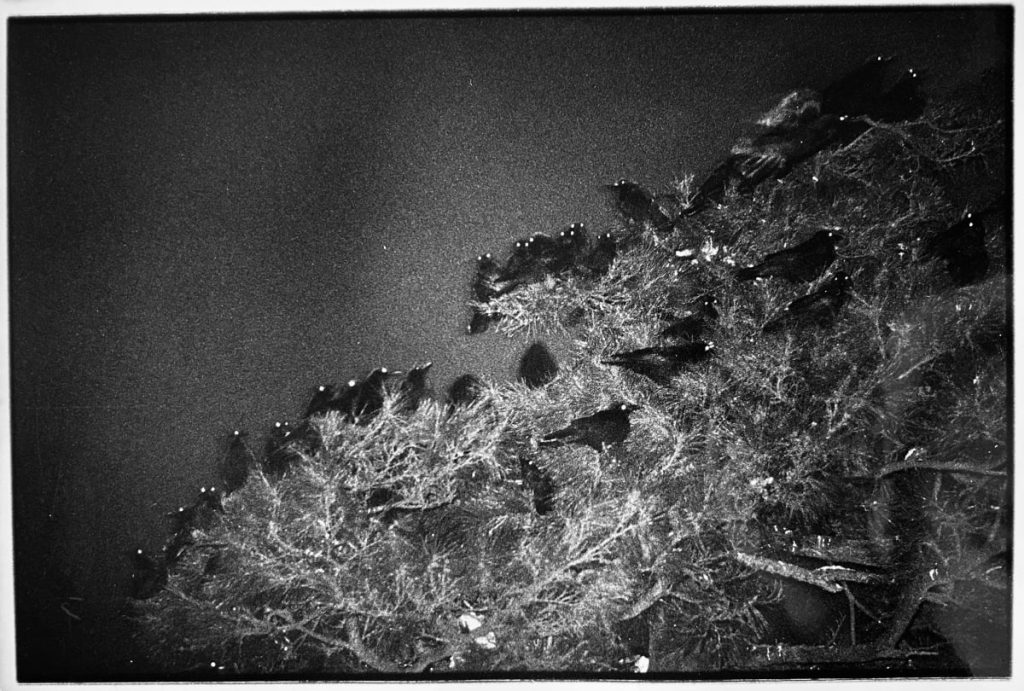

What is it to make a memory out of loss? To distill the precise ache of mourning? Fukashi in a crippling depression find his shadow-clone in ravens, which later becomes his best known work. While reeling from loss of love that comes from ending his thirteen years of marriage, Fukashi takes on a train returning to his hometown of Hokkaido.

Then as a coping mechanism or maybe even fate, Fukase started getting off at stops to capture photos as ravens. In Japanese culture this is as contradictory as the man himself. Ravens are disruptive creatures, omens of turbulent times. But for Fukase, they transformed into symbols of lost love and almost unendurable heartbreak. He became obsessed with them—their darkness, their loneliness. Through them, Fukase found a way to express what words could not—a fractured reflection of a mirror that is set on himself.

The Black

From 1976 to 1985, Fukase’s obsession with ravens consumed him. He photographed them in every state—alive and dead, in flight and at rest. His images were not polished or refined but raw and brimming with emotion. Every photograph seemed to ache with the weight of loss, every grain a reminder of what he could not regain.

Art does not exist in a vacuum, and neither did Fukase’s. His work is a testament to the idea that love can fade to make room for passion, but passion rarely offers the same solace. The ravens, like Yoko before them, became mirrors—fractured, distorted, yet achingly human.

What remains of Fukase is the art he left behind—and the shadows it casts. His images are not simply photographs; they are fragments of a man chasing himself, a fleeting moment, and the echo of a love that could not last.